Close to Catania’s railway sidings and the main station is an unused brick factory called ‘Le Ciminiere’ which has been transformed into a cultural centre. Part of it holds the Museo dello Sbarco in Sicilia, 1943 (1943 Allied Landings in Sicily Museum).

Guides explain in great detail Sicily’s history dating back to the invasions of the Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians etc. but tend to overlook the historical World War II Allied Landing invasion in Sicily on 10th July 1943.

This started off the fascist overthrow in Italy and was the beginning of the end of the Second World War conflict.

The code name was ‘Operation Husky’ and Sicily was chosen for the landing as it was within easy reach of allied fighter planes based in North Africa and Malta who could support the landing troops as the coalition did not have enough aircraft carriers in the Mediterranean.

The Axis powers had previously been deceived into thinking that the landing area would be Sardinia. The British had carried out ‘Operation Mincemeat’ where documents indicating Sardinia and Greece as the next allied targets, fell into the hands of the Germans after they picked up a drowned body of a ‘British officer’ at sea.

The combined forces of 478,000 British, Commonwealth and American troops landed on the beaches from the area of the Gulf of Gela down to the Gulf of Noto. The supreme commander was General Eisenhower with General Patton and the 7th American Army who took the coast between Licata and Scoglitti. The 8th British Army was under General Montgomery’s command and spread themselves over the south-eastern point of the island between Pachino and Siracusa. The British met with fierce German resistance on the Plain of Catania whilst trying to make their way up the Ionian coast. The Americans, instead, gained control of the less fortified western side of the island occupying Palermo and subsequently Messina.

Before the landings, troops were provided with a Soldier’s Guide to Sicily in which the soldiers were warned of the hot scirocco wind that can blow at that time of the year. And it did. Other somewhat questionable information was also given: “Morals are superficially very rigid, being based on the Catholic religion and the Spanish etiquette of Bourbon times…” and even cautions against getting too friendly with the natives: “The Sicilian is still, however, well-known for his extreme jealousy in so far as his women folk are concerned, and in a crisis still resorts to a dagger”.

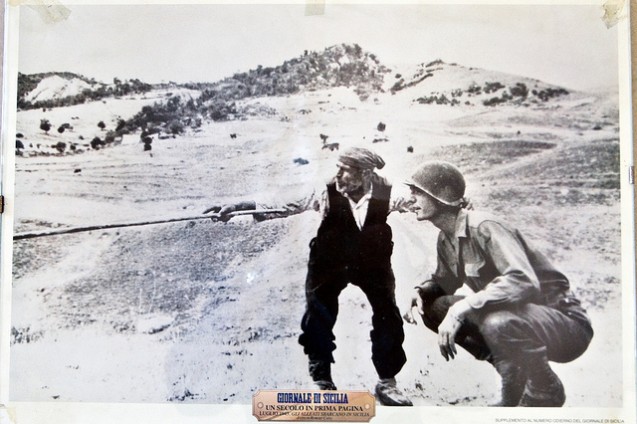

Sicily had been repeatedly bombed since the beginning of the war as the island was Nazi occupied. With a naval blockade in force, food was in very short supply and severe rationing encouraged the black market. The population was extremely tired and hungry so put up little resistance towards the allied invaders. In fact the peasants working in the fields hardly put up their heads, totally indifferent to the fact that the soldiers marching by were liberating the towns and villages over the island. For too long they had been hiding or even living in badly built, insufficient or improvised air-raid shelters. For them it was just a relief that this all meant the beginning of the end of the war.

Much has been said and argued about the Anglo-American secret services who were on the island long before the landings, establishing useful contacts to aid the invasion. This includes whether or not Italo-American and Sicilian Mafia bosses were involved in the operations. Whatever the thoughts it is a certain fact that great importance and power was conferred by AMGOT (Allied Military Government Occupied Territories) on one Mafia boss, Calogero Vizzini. He was appointed mayor of Villalba on 27 July, 1943 which gave a new lease of life to his shady activities.

On September 3rd, 1943 the armistice between the Italians and the Allied Forces was signed in Cassibile near Siracusa. The Supreme Commander, General Eisenhower was also present.

Today many of the concrete pillbox bunkers still remain along that part of the coastline used by the Italians and Germans to defend themselves.

The most poignant memorials, however, are the three manicured, lovingly tended War Cemeteries where the British and Commonwealth troops, who died during their service to their countries, were laid to rest. American soldiers were mostly transported back to the States or moved to the American War Cemetery in Nettuno, near Rome.

In Syracuse War Cemetery, there are 1,059 burials from all over the Commonwealth. Nearly all died in the early stages of the campaign. Many were from the airborne force when their gliders were blown off course back into the sea by gale force winds.

In Catania War Cemetery 2,135 are buried. Many are from the later stages of the campaign and British soldiers killed in the fierce fighting in the Plain of Catania.

In Agira, near Enna, there is the Canadian War Cemetery where 490 Canadians are buried. Agira was taken by the 1st Canadian Division on 28th July 1943 and this site was chosen for the burial of all Canadians who had been killed in the Sicily campaign.

All this and a lot more can be seen in the very well laid out Allied Landings in Sicily Museum. As you enter, a simulated air raid takes place whilst you are sitting in a shelter, recreating the extreme living conditions of that time. Other unexpected moments en- route through the museum are in store, adding to the authenticity of the moment.

As stated in the guide book: “Everything that we have forgotten is now conserved in this museum which aims to protect our most precious asset: peace. War has never ceased, it changes location but the blood-bath continues.”

(More info at Museo dello Sbarco in Sicilia, 1943)